GFL Fine Art is deeply saddened by the news of the recent passing of acclaimed Western Australian artist Miriam Stannage. What follows is an article of recollections by her close friend and colleague Dr. Phillip McNamara.

Miriam Helen Stannage died early Sunday morning (September 11th, 2016). She will be remembered by the art world for her 50 plus years of creativity – in installation, paint, photography, drawing, video and artists books – and affectionately by many artists for her quiet support of their art. Miriam diligently visited local exhibitions for decades, often leaving appreciative reflections in exhibition comments books and taking home catalogues that she inevitably passed on to me for my archives.

Miriam had many long lasting friendships. Ours lasted from 1980 until her death. I first knew of Miriam through the praises of her brother, the historian Tom Stannage (who worked with my father on The People of Perth) and a couple of simple line drawings of hers shown at the upstairs Carroll’s Bookshop Gallery in Hay Street. More formal introductions occurred through my interest in the work of George Duerden, Cliff Jones and the Henry Froudist studio of the mid to late 1960’s.

Cliff and George had both done portraits of Miriam, and a vacuum cleaner spray painting (in greens and yellows) from her 1969 show of abstracts at the Old Fire Station Gallery hung in Cliff’s print making studio. I knew how radical the abstract was for both Perth and Australian art of the period and was smitten. That both these men spoke so admiringly and affectionately about her also impressed me. They informed me that she had been very important for the promotion of modernism in Perth, firstly through setting up her own gallery in 1965 (the Rhode Gallery), and through her work in establishing the Contemporary Art Society with Guy Grey Smith. They were proud that Bernard Smith had controversially chosen one of her spray painted abstracts as the winner of the 1970 Albany Art Prize. This was clearly an independent and self-actualising person.

I became a very close friend of Miriam when I started writing a thesis about the work of Tom Gibbons – Miriam’s husband. Their conversations about art, film, philosophy, religion, art and the art world were perceptive, informative and fun to be a part of. I visited regularly and continued to do so after Tom’s death in 2012. They were very hospitable; Miriam liked Wagon Wheel biscuits and any cake from Ruby’s Patisserie in Tuart Hill.

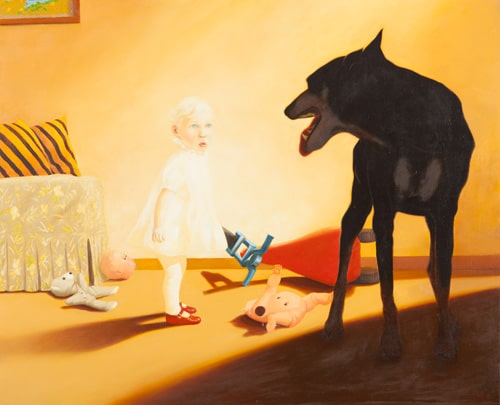

Both Miriam and Tom were mentors in teaching me how to see beauty and poignant mysteriousness in ordinary things. Both had a religious sensibility and saw the everyday world as a celebration of the divine. Both were playful, conceptually witty and intellectually quick, whilst also being disciplined in their art practices.

I admired many things about Miriam. One was that she was very self-reliant and would go off camping by herself in the wheat belt and National Parks. One of her favourite areas was Cape Le Grand National Park near Esperance, so she didn’t mind a drive. She also had fond memories of the Northam area, where she was born in 1939, and she would go see the wild flowers every year between there and New Norcia (work from some of her most significant series are in the Monastery collection there). A pastel drawing of wild flowers by her was one of the first works I ever bought. She loved native gardens and established a fine one at her home. Miriam was also a keen bird watcher and so liked the fact that many species were attracted to her garden. Delighting in being close to nature Miriam either walked along Trigg beach near Mettams Pool, or around one of several lakes near her home, every day.

She was physically very fit, so it was a shock to be told by her that she had a terminal tumour. More so that it came less than a year after she had been named a State Living Treasure.

The last few months of her life demonstrate many of the traits that I loved. Miriam saw the interconnection – the associations, symbolism and archetypal – in all things. It was innate. Hence when she rang me on Easter Sunday and asked me to come see her in person, as she had something important but sad to tell me, I feared the worst. Miriam was also pragmatic and lived life on her own terms so it didn’t surprise me that when we met she also said that she had chosen not to undertake radical treatment and, though it would be a difficult journey, she would let it take its course. She asked me not to tell anyone else as she didn’t want people fussing.

The prognosis was a couple of months so Miriam didn’t expect to see the catalogue she had been working on with Lea Kinsella published, nor know how the accompanying Lawrence Wilson survey exhibition was received. But she was delighted that Lea had been interviewing her regularly for years and that the survey of her most recent significant series was occurring. It was with great satisfaction that we read and discussed the proofs that Ted Snell and Lea expedited to her.

Her situation became more widely known when the exhibition Miriam Stannage: Survey 2006-2016 opened at the Lawrence Wilson in July. By then she was in Hollywood hospital just down the road. There was much poignancy at the opening when people learnt the reason for her absence. On opening night I took Miriam a video that Michele (my wife) made of the occasion. Miriam had been imagining the day and the various proceedings and so we watched the recording of it many times. It may give people some joy to know that Miriam was very pleased with how the show was hung and the celebrative atmosphere of the opening. She recognised many people in the crowd, was delighted for their continued support, and it sparked many conversations about Perth art and exhibitions she had seen over the years.

One regret Miriam voiced to me was that she didn’t have the energy to write the many letters to friends and supporters that she had thought she would whilst in hospice. Miriam wanted people to know that she was very grateful for the kind comments on her art and she wanted to also encourage many younger artists to keep going! I said I’d pass these messages on.

Miriam faced her last journey with great courage and typical wry humour. When I asked about her funeral and whether she wanted me to say anything she said “Just put a pile of Lea’s book up the back and say ‘If you want to know anything about Miriam or her art, everything she wanted to share is in those books, so buy a copy as you leave.’” She added wryly that her archives – including the diaries she wrote in everyday of her life – had already gone to the National Library with a caveat of 25 years on them, so if you wanted to know more you’d have to wait.

Miriam also suggested that, as a last art installation idea and as homage to her Security Notice and surveillance series, I should put a camera sticking up out of the flowers on her coffin and attach an all-seeing eye camera to the front of the lectern. She smiled at the surreal idea that she – as artist – would be with us and “watching with an unblinking eye” as we looked on. She seriously thought about the request for quite a while. She always revised her art before deciding on final configurations, so she played with several ideas before taking the camera poking from the flowers out. She chuckled about the lectern. Eventually she said something along the lines of “There will be children there and some people who might not understand that as an art piece. Who wants to leave a funeral with more questions than answers, perhaps not… there are too many possible reactions and I don’t want to upset people who may already be upset, but it’s a great idea.” We both laughed at the irony because Guy Grey-Smith, in the early 1960’s, had told Tom Gibbons that “art isn’t made with ideas” then Miriam, from the late 1960’s on, had pursued conceptual art throughout her oeuvre.

I already miss her greatly. I loved her dearly. She is a major Australian artist. She didn’t want to make a fuss… yet the legacy of her art oeuvre will continue to intrigue audiences for many generations on.

Phillip McNamara